Since I’ve finished my dissertation (whoop!), I’ve been researching and collecting records related to my next project, on the material history of hearing aids. It’s so easy to get side tracked in the digital collections, especially since there are thousands of wonderful historical materials just waiting for some attention. One incredible distraction for me has been the Drexel University College of Medicine Archives & Special Collections, which holds a remarkable repository on women physicians from the 1850s to 1870s.

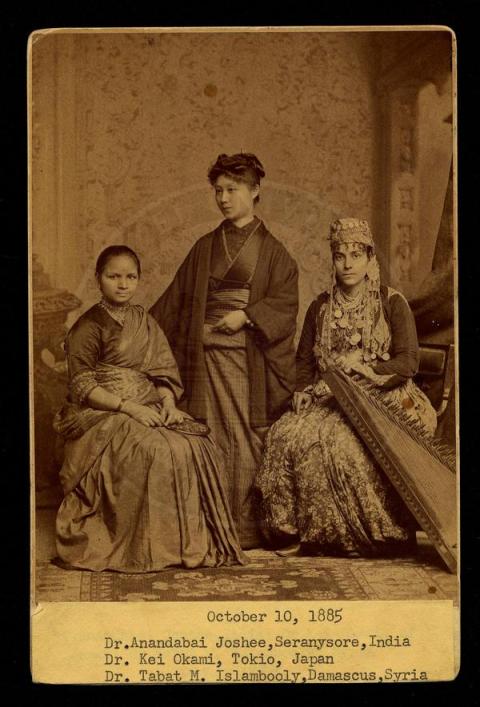

Browsing through the photographic collection, I came across one photograph that piqued my interest:

The photo of the three physicians was a memento from the Dean’s reception, dated October 10, 1885. I have hardly come across sources from the late nineteenth-century featuring ethnic women practicing medicine, especially Indian women. So naturally, I started digging a bit into female Indian physicians, beginning with Dr. Anandi Gopal Joshi.

Joshi was the first Hindu Brahmin females to receive an education abroad and obtain a medical degree. Born in 1865 in Kaylan, a small town near Bombay (Mumbai), she was married off at 9 years old to 29 year old postmaster Gopalro (Gopal Vinayak Joshi), a widower. Gopal renamed Joshi, shifting her birth name from Yamuna to Anandi (“the happy one”). He was also a supporter of women’s education and started teaching his young wife shortly after they got married. She eventually learned Sanskrit and English. The marriage completely ideal; there’s sources indicating that Gopal often abused his young wife in order to keep her focused on her education.

In the 1880s, with the help of a Philadelphia missionary, Joshi was sent to the United States to receive an education in medicine, a decision made after the tragic death of her son when she was 14. She enrolled in the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, then the first hospital for women; her thesis was titled Obstetrics among Aryan Hindoos.

Joshi’s letter to Alfred Jones, member of the Executive Committee of the Women’s College 1883. She writes for permission to attend the College, and for financial assistance.

Joshi earned her M.D. at 21 years old. In 1886, at her husband’s urging, she returned to India, where she took up a post at the Albert Edward Hospital in Kolhapur. She died a mere year later from tuberculosis.

I’m so fascinated by this story. A young woman, encouraged (if not forced), to educate herself, travel to a faraway land and learn medicine. She, among others, is a voice of our historical past that needs to be heard, and heard frequently. A year after Joshi died, the feminist writer Caroline Wells Healy Dall (1822-1912) penned her biography, The Life of Dr. Anandabai Joshee, a Kinswoman of the Pundita Ramabai. A fictionalized account of Joshi’s life was also written, by S.J. Joshi in 1962, Anandi Gopal. Originally written in Marathi, the novel was eventually adapted into an award-winning play by Ram G. Joglekar.

Joshi certainly wasn’t the only female who studied at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

Gurubai Karmarkar (d.1932) was the second Indian woman to graduate from the college, in 1892. She eventually returned to Indian and worked at the American Marathi Mission in Bombay.

UPDATE: I wrote a second post with more details on Karmarkar.

Dora Chatterjee was also a graduate from the Women’s College, graduating in 1901, being the third Indian women to do so. After graduation, she returned to Hoshyarpur, Punjab, where she worked for a Christian missionary.

UPDATE: For more on Dora Chatterjee, see my third post on this series.

This is all I got so far in my adventures through the digital archives. More another time–for now, back to the project!

All photos from Drexel University College Archives & Special Collections

This is fasciniating, Jaipreet. The relationship between Ananda Gopal Joshi and her husband appears to more like that of a child and an overbearing father! Do you think that Joshi was accorded any special privileges in being sent abroad for medical studies as a Brahmin? Could this still have happened if she was from a lower caste even although from a background of some affluence?

LikeLike

Hi Iain, thanks for the comment.

From what I’ve briefly read, when Joshi’s husband took up a position in Calcutta, there was strong discrimination against women being educated. This meant that Joshi’s options for education were limited.

Gopal wrote to a missionary named Royal Wilder in the United States, a missionary to assist them in relocating so Joshi could study medicine. They refused Wilder’s condition to convert to Christianity. However, Theodicia Carpenter from New Jersey saw the correspondence between Gopal & Wilder, which was printed in a local paper–she offered Joshi the assistance she required.

It appears that just getting the journey to America was difficult and that Joshi wasn’t afforded any special privileges, regardless of her high caste. It’ll be really interesting to dig deeper into women’s positions and education in India during this period–and how opportunities abroad could increase their status. All the women I mention in this post returned to India with their studies. I wonder if the same is also true for Indian women in Britain? Men were often sent to Britain to study medicine and law, did women did too, during this period?

LikeLike

Also worthy of note some female Indian doctors trained within Indian institutions at the time, being among the first to be formally educated in medicine in the British empire.

Kadambini Ganguly: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kadambini_Ganguly

Chandramukhi Basu: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chandramukhi_Basu

LikeLike

I’d be a little careful about painting privilege over caste with too broad a brush. Sure, higher caste in general provided (and provides) a greater position in society. But women in lower castes could (can) sometimes be more free due to fewer structures on ritual purity, lower social risk for the family, etc. I also find interesting the mention of conversion as precondition of help: a low-caste person had (has) less to lose from a conversion. A Brahmin might face ostracism or worse. Caste is possibly more subtle than, say, race and class. On the margins it can unexpectedly cut across the grain.

Also, re “overbearing father”, from a modern/western perspective, “overbearing” is practically a redundancy 🙂

All in all, a very interesting post.

LikeLike

Thanks for posting very interesting pictures and history from archives. Actually, Dr. Anandibai Joshi is quite famous in Maharashtra, India where she originated from. In 80s, there have been many articles, a novel (Anandi-Gopal) and play (Anandi-Gopal) based on her life as well her complex relationship with her husband Gopal Joshi. Mr. Joshi was quite eccentric and on one hand he pushed Anandibai towards getting a medical education on the other hand he was traditional. Interesting fact is that he was always at loggerheads with other traditional brahmins at that time, which is evident from his newspaper articles at that time. Anandibai was quite a remarkable women and hats off to her for leading the way.

LikeLike